Written by: Anonymous (she/her).

Edited by: Zahra Taboun (she/her).

Note: The author refers to women in the piece to self-identify and as a way to describe people who may get an abortion, but we want to acknowledge that not all folks who get an abortion identify as a woman.

Because my abortion was (as far as I know) clinically unremarkable, because choosing to get an abortion was not a decision that would have changed had circumstances been different, and because I never had a moment where I thought it might not be the best course of action for me, it never occurred to me that it would be impactful.

At first, I was bit nervous about accessing abortion services. While I knew I could get an abortion if I needed one, because I had gone through such a large part of my adult life without ever being unwillingly pregnant, I hadn’t given the actual logistics of accessing abortion much thought. It was a matter of political discourse to me: Pro-choice, always; Accessible, always; with dignity, always. So, not knowing how far along I was in my pregnancy, when the office assistant at my GP’s office told me it’d be three weeks before I could get an appointment, I nearly panicked. Additionally, not knowing my GP well and living in a relatively Catholic rural town (which, no less, has a hospital that will not perform surgical abortions for religious reasons) I didn’t know, for instance, if she’d be a conscientious objector or if I would run into any other barriers. So, I looked online and learned about the self-referral process in my area and submitted my information. Within 24 hours, a nurse called me to organize everything. I imagine it was completely unintentional, but the “oh” in response to her asking me why I needed a referral was the first instance where I felt judged, but I didn’t really care in that particular instance.

Even though I probably didn’t have to, I traveled over 100 km from home to a hospital in the province for bloodwork and the ultrasound. Those were scheduled about a week after I called the self-referral line. I found it weirdly reassuring that at every step, I did not emotionally stumble. Even when the ultrasound technologist showed me the picture of my fetus, I felt nothing. I didn’t prevent myself from having an emotional reaction, but I wanted to know whether I would, and I just didn’t. There was a moment when I wondered whether the ultrasound technologist wanted me to have a reaction or not. She did not let on either way.

I didn’t expect to ruminate on the abortion afterwards or get angry. After all, everything went largely well. The frustration got worse when I started reading pro-choice literature or posts online, thinking initially it would bring me feelings of community, relief, and solace. The stories I read tended to be heart-wrenching narratives of women who spent their time justifying how much they needed the abortion: that they were in school or in a bad relationship or poor or mentally fragile (the list goes on). I also kept coming across well-intentioned arguments against pro-lifers, which were focused on what we lose as a society when women who have children leave the public participation.

There are numerous statistics about how women’s participation in the workforce and public life improves societies, but what these arguments did for me, was give me the incredible need to justify my abortion. Without adequate achievements to point to, I felt like an immense and shameful failure.

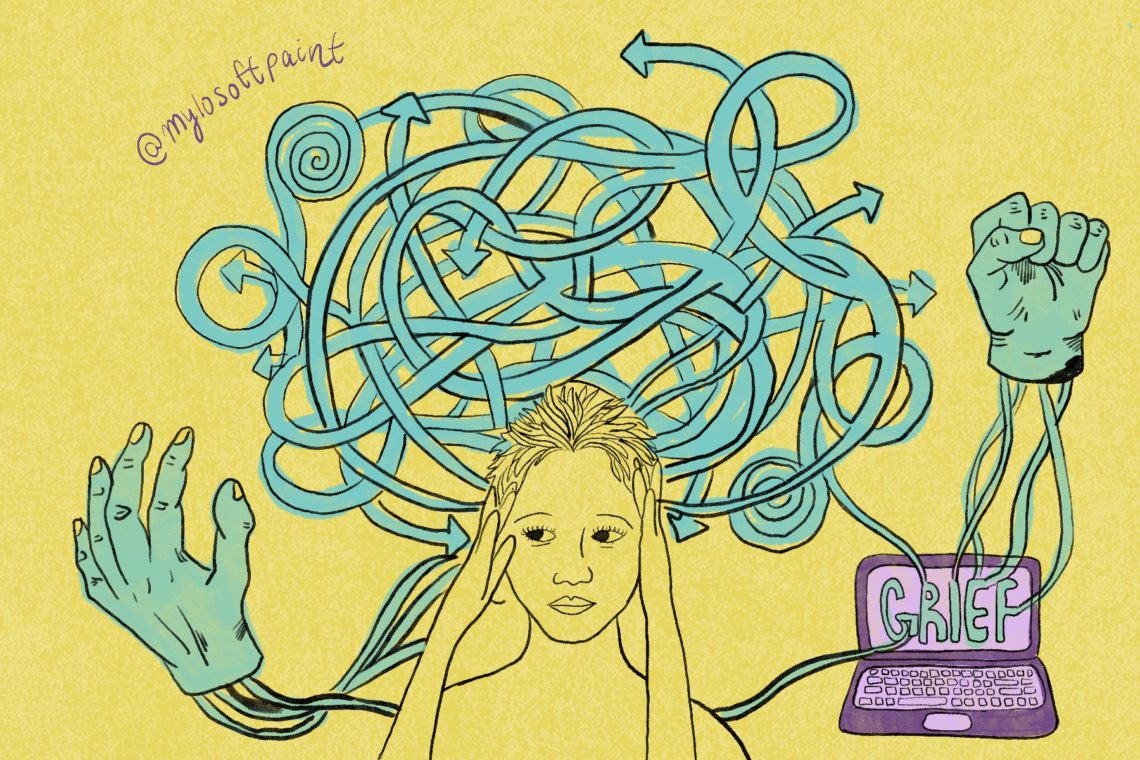

Who would care if I left the workforce temporarily or indefinitely? What have I been doing for my community or the world since I’m not hindered by the all-consuming responsibilities of raising a child? Who would be proud of what I’ve accomplished, with meaningless hobbies and an unremarkable career? Then again, I am a staunch feminist who believes that abortion is a right, so my anger and guilt was compounded by the fact that I felt I shouldn’t feel guilty in the first place. I convinced myself that every tear was a betrayal to the values I espoused. My grief, which lasted a couple of months, wasn’t one of chosen loss or about the abortion itself. It was that narratives about abortion forcefully and painfully made me reflect on my self-perceived inadequacies.

I wouldn’t have spoken to anyone about my struggle had it not been for my spouse’s encouragement to speak to my doctor. I had a phone referral for an IUD placement, so I’d be talking with my new doctor shortly anyway, and I decided I’d mention it then. I was nervous, so I phrased it as a physiological issue: could my hormone levels still be affecting me the way they were when I was pregnant? It was clumsy and embarrassing to look back on, but it was easier than saying that I couldn’t stop crying. The consult wasn’t really a consult in the end because I didn’t care about the differences between Skyla and Mirena. I made it weird for the both of us, but she handled the situation with as much tact and grace as could be expected when you’re expecting a normal phone consult and instead you get someone incoherently asking you why they can’t stop sobbing and refusing to believe you when you say they went through something. The awkwardness felt on the other end of the line was palpable and I know she didn’t want to be having the conversation at all, but I didn’t feel judgment.

She recommended counselling. Admitting to needing counselling brought up the same feelings that crying in the first place brought up: that I was giving credibility to pro-lifers and unfounded diagnoses of “post-abortion grief” and that I was, yet again, not living up to the image I had of myself. Through tears, I told the social worker on the other end of the line that I got exactly what I wanted. Being told that what I went through sucked and that mattered, that I didn’t actually get everything I wanted because I didn’t want to get pregnant in the first place, that I could grieve anyway, that I didn’t want to shoulder the burden that is making a monumental decision all on my own, and that to it, but it doesn’t. It just shifts the pressure.

I didn’t actually deserve to be subjected to the societal stigma that a woman needs to either be a mother or a superstar to matter

I thought either about my experience or the feelings that it brought up every day for almost a year. I’m left convinced that it’s important to do more than say that abortion is normal. Even though I knew the often-cited statistic that 1 in 3 people with uteruses will have an abortion by the age of 40, it still feels incredibly lonely. I didn’t know that, even though I have no regret, I could feel an injustice that while others would be willing and happy to carry a baby, all the while celebrated by loved ones, I’d instead be left alone to rebuild my sense of self-esteem and purpose that were crushed by the emotional aftershocks of my abortion. I told a few people about my abortion. I haven’t told anyone that it left me shaken and with an unsteady sense of purpose. I don’t think I will. As we normalize abortion, we also need to be mindful that the narratives we promote as justification are not bound up with weighty expectations of certain versions of being childfree. We shouldn’t tie up what is and should remain an unequivocal right with certain narratives we find morally appealing about why people have abortion. And, so that if a person unexpectedly struggles afterwards with their own story, we are equipped to help instead of leaving them to wonder where the hell any of this came from.