Written by: Bobbie Martin (she/her), OT.

Edited by: Étienne Maes (he/him).

Dear readers, my name is Bobbie! I am a white settler currently living and working as an Occupational Therapist on unceded Mi’kmaq territory in Kjipuktuk. Throughout this piece I touch on the colonial and oppressive history, and ongoing practices of Occupational Therapy (OT) as it relates to sexual health. I want to acknowledge that I am a white, able-bodied, cis-woman with my own bias and privilege. Most of my learning about anti-oppression, social justice, and sexual health comes from brilliant trans, nonbinary, queer, and disabled educators, activists, and scholars (see resource list).

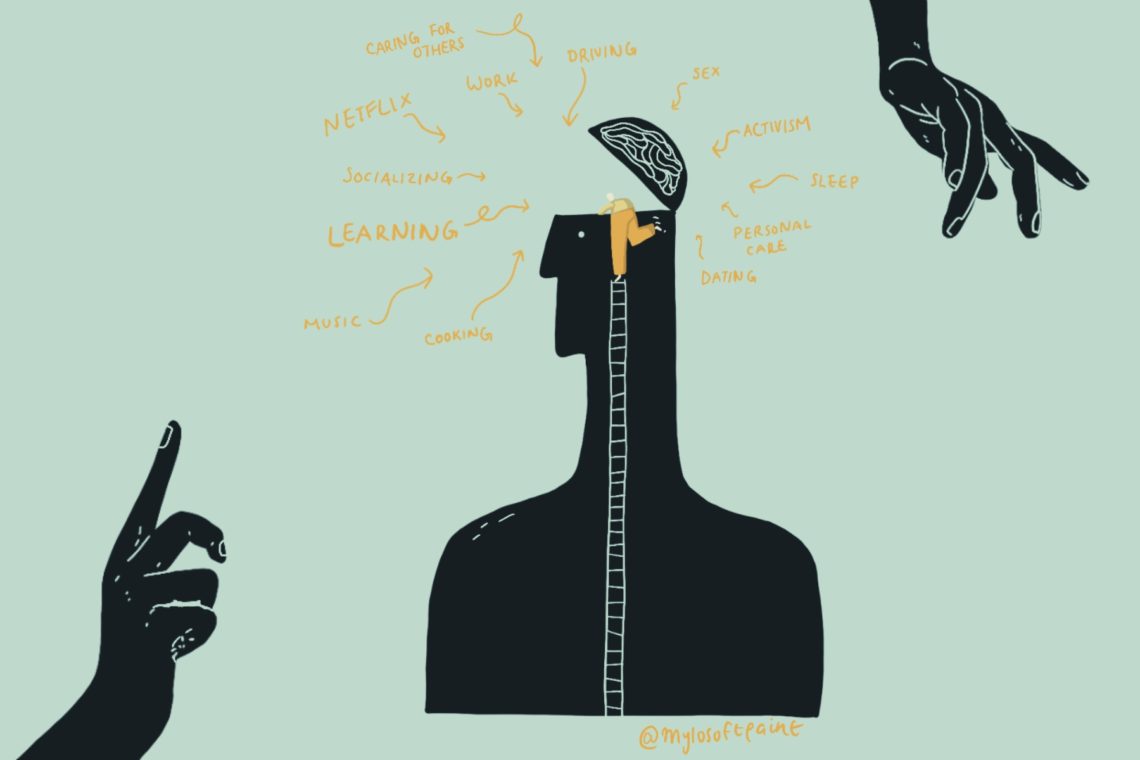

Throughout my OT education there was very little mentioned about sex, sexuality, and sexual health. I remember a few slides within one lecture that discussed sex as an Activity of Daily Living (ADL). Unfortunately, discussing the topic of sex as a meaningful and important ADL was short lived and most of the sexual health education focused on the lack of research and practice guidelines available in OT. The absence of sexual health training continued into my fieldwork experiences where sex was rarely addressed with clients. This was frustrating as I believe OTs have the potential and ability to address sexual health (i.e., pelvic and menstrual health) and sexuality (i.e., sex, relationships, consent, intimacy) at the individual, social, environmental, and systems level of health. OTs with further education in sexual health address sexual health concerns more frequently and feel more comfortable addressing the topic with clients. This is important as clients often want their OTs to be able to address their sexual health needs (1, 2). As OTs we need to recognize the gaps in our knowledge, educate ourselves and push for more up-to-date, comprehensive sexual health education in OT.

Discussing the topic of sex as a meaningful and important ADL was short lived.

The absence of sexual health education in OT may be based in the history of the profession. The inclusion of sexual health education and the practice of addressing sexual health in OT has historically been debated within the field (3). This contention has been tied to the historical and political views of the profession, particularly with respect to OT being grounded in white, colonial, middle-class, able bodied, hetero-cis-normative ways (4,5). Furthermore, the hesitation to discuss sexuality in OT has been traced to the profession’s values being historically rooted in white, hetero-cis-normative, middle-class values in which sex and sexuality are restricted to the private and forbidden domain (4). A common social discourse throughout Canadian healthcare has been one that limits the right to sexuality to young, white, heterosexual, cisgender men and denies the right to sexuality to those who do not fit this model (3,4,6). There are many reasons that these values and structures continue to be upheld and perpetuated in OT, such as: the lack of disability justice and anti-racist frameworks, the lack of anti-oppressive institutional policies, and the overall lack of diversity within the field of OT.

OTs need to be learning about the ways in which these oppressive structures are still upheld and perpetuated within the profession.

Although individual OTs may not explicitly hold these values, the profession’s colonial history, unaddressed ableism, and society’s general ignorance with disability and sexuality has led to a relative silencing of sexual health within OT (2, 5-7). OTs need to be naming and recognizing the history of the profession, the historical harm the profession has caused to marginalized populations and learning about the ways in which these oppressive structures are still upheld and perpetuated within OT. All of this needs to be happening in concert with developing and implementing comprehensive sexual health education into the OT curriculum. The profession of OT needs to be centering and partnering with grassroots organizations when addressing the gaps in OT’s sexual health education. Disabled Activists and Sexual Health Educators often state that healthcare practitioners and able-bodied communities have much to learn from the disabled community around sex, sexuality, and sexual health (i.e., communication practices and creative solutions, and practices grounded in pleasure) (2, 8). OT needs to be learning, centering, and collaborating with the work of disabled communities especially Black, Indigenous, 2SLGBTQIA+ disabled communities when developing and delivering comprehensive sexual health education in OT.

So, what is currently going on in the OT profession with respect to sexuality and sexual health?

Research shows that OTs generally agree that sexuality is an important part of many people’s lives and that sex is a meaningful occupation which should be addressed within OT practice (4,6,7). The research simultaneously shows that in practice OTs rarely address clients’ sexual health concerns or meaningful sexual occupations (4,6,7). The exclusion of sexual health within OT practice has serious consequences for clients — i.e., a client’s intimacy and sexual activity wants and needs not being met or a client’s pelvic health concerns being ignored (a profession that focuses on toileting, self-care, and sex can and should address pelvic and menstrual health). Fortunately, there are many resources out there that OTs can learn from, one being the podcast “Handicast” hosted by Andrew Gurza and Heather Morrison. This podcast is brilliant, with episodes focusing on disabled people’s experiences with OTs as well as OTs discussing sex and disability. See the resource list below for more OT and sexual health information and education!

In practice OTs rarely address clients’ sexual health concerns or meaningful sexual occupations.

Overall, the evidence I have found suggests that the lack of comprehensive sexual health education in tandem with the OT profession being rooted in colonial, cis-normative, and ableist ways inevitably account for some of the reasons why sexuality and sexual health are not part of the service agenda in many OT settings (2-6,9). The profession of OT has a lot of transforming and accountability to undergo; there are no quick and easy solutions to creating more comprehensive sexual health education, training, and service provision within OT.

I want to reiterate that I am no expert in comprehensive sexual health education and much of my learning about the intersections of social justice and sexual health come from brilliant trans, nonbinary, queer, and disabled educators, activists, and scholars. I have provided resources below that I found helpful in my learning.

Here are some further resources:

Educational Resources for OTs:

- Sex, Love, and OT

- Sex Intimacy OT

- Functional Pelvis

- Coalition of Occupational Therapy Advocates for Diversity

- OT After Dark Podcast

- Decolonizing Sexual Health

- Handicast

Sexual Health Organizations in Halifax:

- Halifax Sexual Health Centre

- South House Sexual and Gender Resource Centre

- Venus Envy Halifax

- Imwithperiods

- Youth Project

- Steppingstone

- Autism, NS

Community Facilitators and Sexual Health Educators in Halifax:

- Rachele Manett

- Frank Heimpel

- Aaliyah Paris

- Carmel Farahbakhsh

- Arielle Twist

- Kate MacDonald

- Francesca Ekwuyasi

References:

1. Helland Y, Garratt A, Kjeken I, Kvien TK, Dagfinrud H. Current practice and barriers to the management of sexual issues in rheumatology: results of a survey of health professionals. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2013 Jan 1;42(1):20-6.

2. Gurza, A, Morrison, H. “Sitting Down w Occupational Therapist Anita Brown Major [podcast on the internet]. Canada: The Handicast; 2020 [updated 2020 Nov; cited 2021 Feb 19]. Available from:https://disability-after-dark.pinecast.co/episode/953957dd181f4df2/the-handicast-episode-8-sitting-down-w-occupational-therapist-anita-brown-major

3. Couldrick L. Sexual expression and occupational therapy. British journal of occupational therapy. 2005 Jul;68(7):315-8.

4. Mc Grath M, Sakellariou D. Why has so little progress been made in the practice of occupational therapy in relation to sexuality?. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016 Jan 1;70(1):7001360010p1-5.

5. Hammell KW. Sacred texts: A sceptical exploration of the assumptions underpinning theories of occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009 Feb;76(1):6-13.

6. Young K, Dodington A, Smith C, Heck CS. Addressing clients’ sexual health in occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2020 Feb;87(1):52-62.

7. Rose N, Hughes C. Addressing sex in occupational therapy: A coconstructed autoethnography. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018 May 1;72(3):7203205070p1-6

8. Rent S. “We know our bodies well and what works”: people with disabilities help design prototypes for sex toys. Halifax Examiner (Canada) [serial online]. 2021 Feb 9 [cited 2020 Feb 19]; Available from: www.halifaxexaminer.ca/featured/we-know-our-bodies-well-and-what-works-people-with-disabilities-help-design-prototypes-for-sex-toys/

9. Esmail, S, Darry K, Walter A, Knupp, H. Attitudes and perceptions towards disability and sexuliaty. Disability and rehabilitation. 2010 Jan 1;32(14):1148-55.