Written by: Saleem Razack (he/him), MD.

Edited by: Zahra Taboun (she/her).

I came of age as a Brown Gay man in the late 80’s and early 90’s. Medical school kept me artificially young and closeted for longer than most, but I definitely knew who I was, was very horny, and felt that just over the next corner, there would be something “more”. I just didn’t know what that something “more” was.

The official story is that I came to Montreal from Toronto to undertake a residency in pediatrics and then subsequently subspecialized and “stayed on” as a staff member. That is kind of true, but there is a truer reason I came–I came to Montreal to be Gay. I needed the distance of some 540 km to cut a very tight, very loving, and very long immigrant umbilical cord, which had been attached for perhaps 25 years longer than it should have been.

Medical school kept me artificially young and closeted for longer than most, but I definitely knew who I was.

I hit the Montreal Gay scene with a lot of vim and vigour in those early years. Perhaps it was making up for lost time. It was lovely. There was a part of it that always has given me pause to reflect. I was a wiry Brown young man and it got me some attention. I would regularly be chatted up in bars with the assumption on the part of the one giving me attention that I was “Le petit Arabe” (“The Little Arab Boy”), repressed, with all of this pent up sexuality. I was neither Arab nor repressed, but I certainly played the part. I tried to be one of the boys in the homoerotic orientalist paintings of Jean Léon Gérôme or Armand-Philippe-Joseph Bera, waiting patiently for the gaze of the European male to fall upon me.

I admit, this kind of Orientalism, to use Edward Said’s analysis of the European gaze cast upon the foreign and exotic cultures of the mythical “East”, got me dates. But after the 300th or 400th time of objectification, it got a little stale.

What I was experiencing was the whiteness of queer culture in Montreal. It did things like assume I was repressed, or that I had to leave my Muslimness and Brownness behind, possibly with all of my family members, in order to participate in it. It said, we welcome you (kind of), but you’ve got to be like us, and forget about all of your smelly food. When we need a fix of that, we’ll order Indian take away. Butter chicken is the best!

This whiteness was not just relational; it was and is structural. It is there in the controversies of the inclusiveness of pride parades – how does Pride intersect with #BlackLivesMatter? What is the white supremacy in the policies, procedures and concerns of 2SLGBTQIA* activist organizations? Why were the Queer voices of colour not centred in the movie “Stonewall”? These are questions that many of us continue to struggle with today.

These experiences need to be understood as threats to identity and ultimately to mental health. I want health care professionals that I consult with problems or concerns to see me as a complex being with multiple intersecting identities. I would like them to be equipped with the critical and structural consciousness to see the pervasiveness of white supremacy in how thinking, clinical reasoning, and indeed, organizations are ordered and structured. Without these skills and habits of mind, care for diverse Queer persons risks being unsafe, traumatizing, and something to avoid.

I want health care professionals that I consult with problems or concerns to see me as a complex being with multiple intersecting identities.

The sexual invisibility that comes with ageing has been a bit of a pill to swallow, but overall has been liberating. I have had the opportunity to call my own bullshit. Way back, when I was receiving that kind of attention of the European gaze (not all the time but lots of times), I struggled to find space for the conflicting positive feelings of receiving attention in the first place, with the negative feeling of objectification. I used to think that, at some point, I would have to find the Brown in Gay – to carve a space for me and people like me that is affirming of our humanity and unique subjectivities.

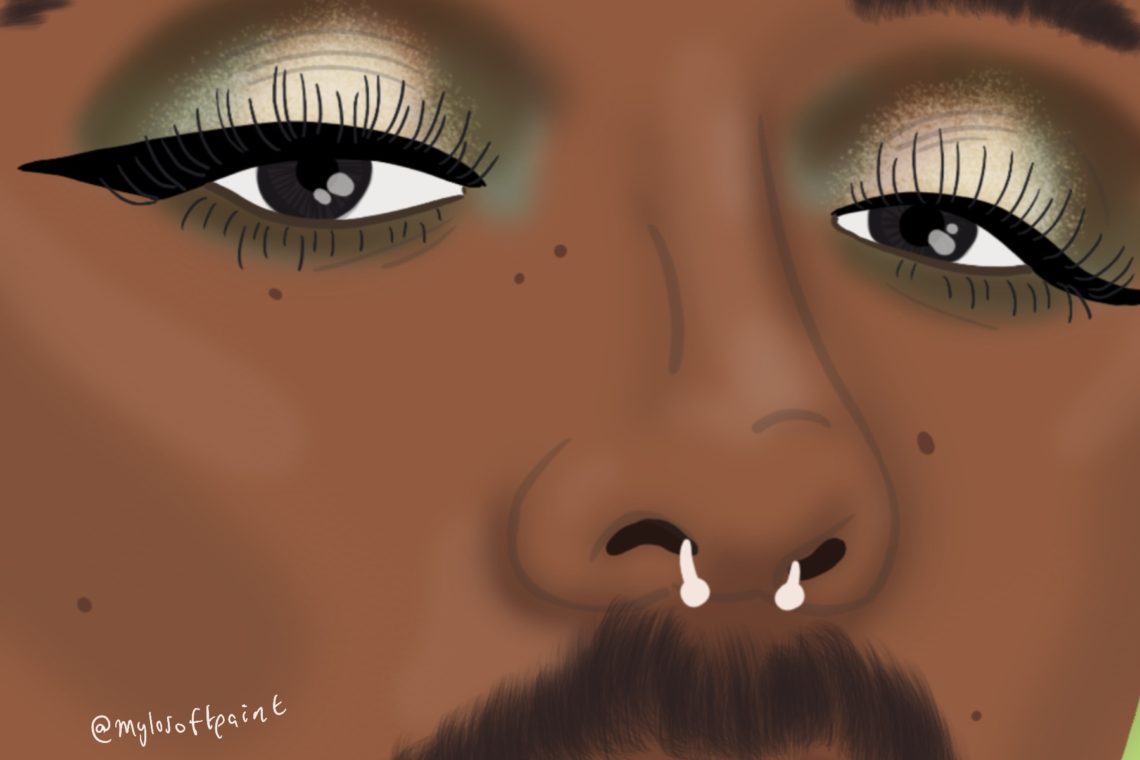

That is true, but I actually think the real “rub” is not to find the “Brown in Gay” but rather to find the “Gay in Brown”. What I need to do is situate myself within a venerable and meaningful history. We Brown Queer People have always been here. We were there when the Sufi mystic, Rumi, wrote his homoerotic poetry to his “Beloved”, Shams-i-Tabrizand. We were there, perhaps when two Madrassah boys got it on surreptitiously in a long-ago India. I am part of this venerable history, and my hope is that the health professional who cares for me is able to see me in all of this complexity.