Written by: Paul MacPherson (he/him), PhD, MD, FRCPC.

Edited by: Etienne Maes (he/him).

While most healthcare providers strive to deliver patient-centered care, when it comes to minorities, many feel uninformed about the specific health issues and the broader social determinants of health affecting different populations. Providing care to gay and other men who have sex with men (GMSM) can be one such challenge. Indeed, several studies have shown physicians often feel they lack the skills, knowledge and experience to provide care to sexual minorities (Kitts, 2010; Knight et al., 2014; Stott, 2013). In a recent survey we conducted of 674 GMSM living in Eastern Ontario, 87% reported having a primary healthcare provider and of those 87% saw their provider at least once per year. Yet, despite this level of healthcare engagement, the prevalence of anxiety, depression, substance use and sexually transmitted infections among these men were notably higher than in the general population (Charest et al., 2021). This raises the question, if GMSM are as engaged in healthcare, why is their health not on par with their heterosexual peers? Our work in Ottawa has identified two substantive barriers that get in the way: a lack of trust on the part of GMSM and a lack of knowledge on the part of healthcare providers.

Many GMSM are wary of healthcare providers and of the healthcare system. In a series of focus groups we conducted with GMSM ranging in age from under 30 to over 60, many expressed a fear of judgment and discrimination by healthcare providers. A number of these men worried that if they disclosed their sexual orientation, they would be subjected to stereotypes and that their health would not be a priority (Haines et al., 2021). These concerns seem pervasive as in our survey of GMSM living in Eastern Ontario, 24% of respondents had in fact not disclosed their sexual orientation to their primary care provider. This choice to not disclose rose to 40% among GMSM living in small towns and rural settings, and to 84% among bisexual men (Charest et al., 2021).

GMSM expressed a clear sense that many healthcare providers lacked knowledge about specific health issues relevant to them.

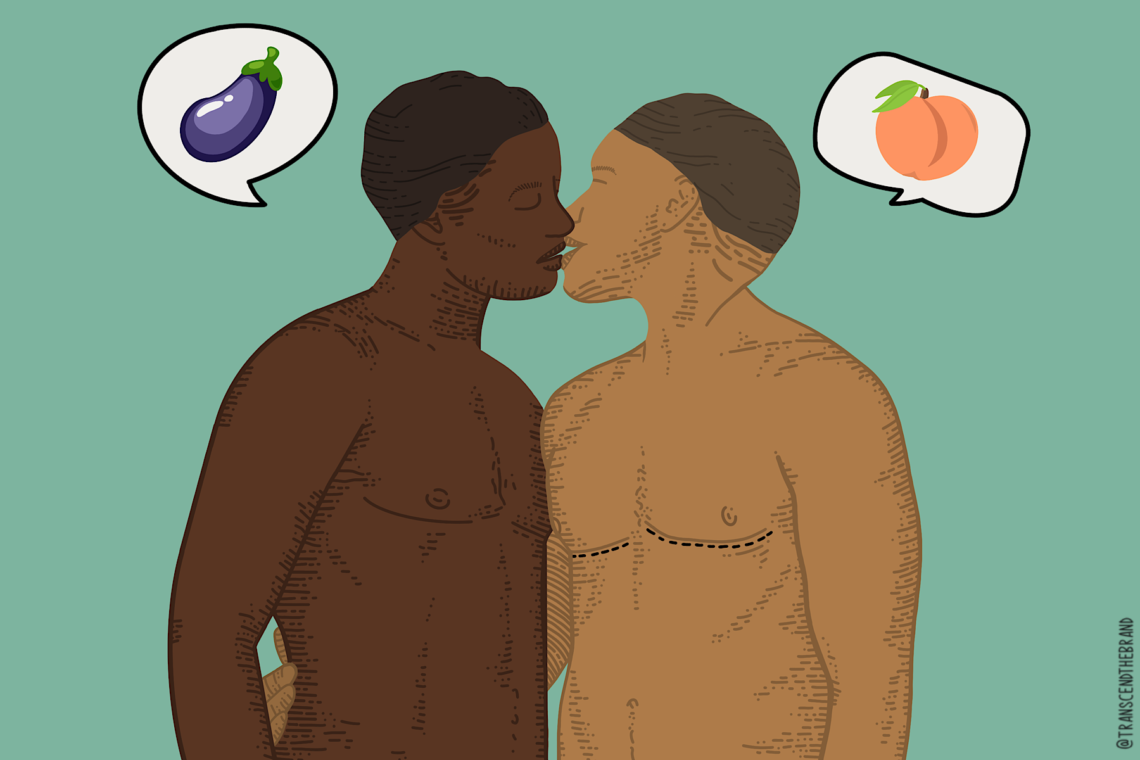

Two areas of particular note were a lack of education on sex between men and specifically about anal sex, and a lack of knowledge about life context and minority stress (Haines et al., 2021). Participants in our focus groups noted how healthcare providers actively avoided discussing sex between men and that the information that was provided was often incongruent with the participants’ own experience. These concerns were substantiated in a survey we administered to 29 physicians and nurses. Within this group, 20% believed receptive anal sex was painful and caused fecal incontinence, 17% believed bleeding after receptive anal intercourse was normal due to trauma, and 14% believed the insertive and receptive roles during anal intercourse are determined by who assumes the male and female roles in a gay relationship and that insertive anal sex was a form of sexual domination (unpublished). In terms of minority stress, focus group participants felt healthcare providers were generally unaware of issues faced by GMSM such as heterosexism, internalized homophobia and the stresses of coming out (Haines et al, 2021). Notably, in our survey of GMSM in and around Ottawa, 14% scored above the cut off for depression and 19% above the cut off for anxiety using the PHQ2 and GAD2 respectively. While the prevalence of depression and anxiety among GMSM is much higher than in the general population (depression: 6%; anxiety 2%), only 13% of the men in our survey had seen a psychologist or psychiatrist in the last 6 months (Charest et al., 2021).

In addition to barriers, our focus group participants also identified three key facilitators they felt would improve healthcare delivery to GMSM (Haines et al., 2021). First, they underscored the importance of creating safe spaces where GMSM are welcomed and openly recognized. They emphasized acceptance over tolerance. As a way to help create a welcoming environment, 44% of GMSM in our survey indicated a pride flag in the clinic or at the front door would make them feel more comfortable visiting healthcare professionals (Charest et al., 2021). Second, focus group members felt healthcare providers need to cultivate and demonstrate a supportive therapeutic relationship with their GMSM patients. This included a willingness to address health issues specific to GMSM and, in cases where a healthcare provider may not know the answer, rather than avoid the topic or refer on, they should seek information and bring it back to the patient. Finally, focus group participants also felt healthcare providers should pay particular attention to issues of disclosure and confidentiality. Of the 674 respondents to our survey, 57% lived in some degree of secrecy and had not disclosed their sexual orientation to at least some of their family, friends and/or peers and coworkers (Charest et al., 2021). It is important then that healthcare providers know where their GMSM patients stand in terms of being out and ensure their patients maintain control over disclosure.

If GMSM are as engaged in healthcare, why is their health not on par with their heterosexual peers?

Delivery of healthcare to GMSM then is hampered by a sense of wariness and distrust on the part of GMSM and by a lack of knowledge about relevant health issues and minority stress on the part of healthcare providers. These barriers though could be easily overcome by creating welcoming spaces where GMSM are acknowledged and recognized, by creating strong therapeutic relationships where health issues unique to GMSM can be addressed with a sense of comfort, and by ensuring confidentiality and attention to disclosure. For healthcare providers delivering care to GMSM, knowing everything may not be the goal and is likely not reasonable. Acceptance and a willingness to learn though, will lay the path.

References:

1. Kitts, R. L. (2010). Barriers to optimal care between physicians and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescent patients. J Homosex, 57(6), 730-747. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2010.485872

2. Knight, R. E., Shoveller, J. A., Carson, A. M., & Contreras-Whitney, J. G. (2014). Examining clinicians’ experiences providing sexual health services for LGBTQ youth: considering social and structural determinants of health in clinical practice. Health Educ Res, 29(4), 662-670. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt116

3. Stott, D. B. (2013). The training needs of general practitioners in the exploration of sexual health matters and providing sexual healthcare to lesbian, gay and bisexual patients. Med Teach, 35(9), 752-759. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2013.801943

4. Charest, M., Razmjou, s., O’Byrne, P., Balfour, L., & MacPherson, P. (2021) The Health of Men Who Have Sex with Men in Eastern Ontario: Looking Beyond Sexual Risk and the Gay, Urban Core. (submitted).

5. Haines, M., O’Byrne, P., & MacPherson, P. (2021) Gay, Bisexual, and other Men Who Have Sex with Men: Barriers and Facilitators to Healthcare Access in Ottawa. Can J Hum Sex (accepted).