Written by: Dr. Jessica Wood (she/her), PhD, Research Specialist SIECCAN.

Questions by: Bobbie Martin (she/her).

Edited by: Danielle LeBlanc (she/her).

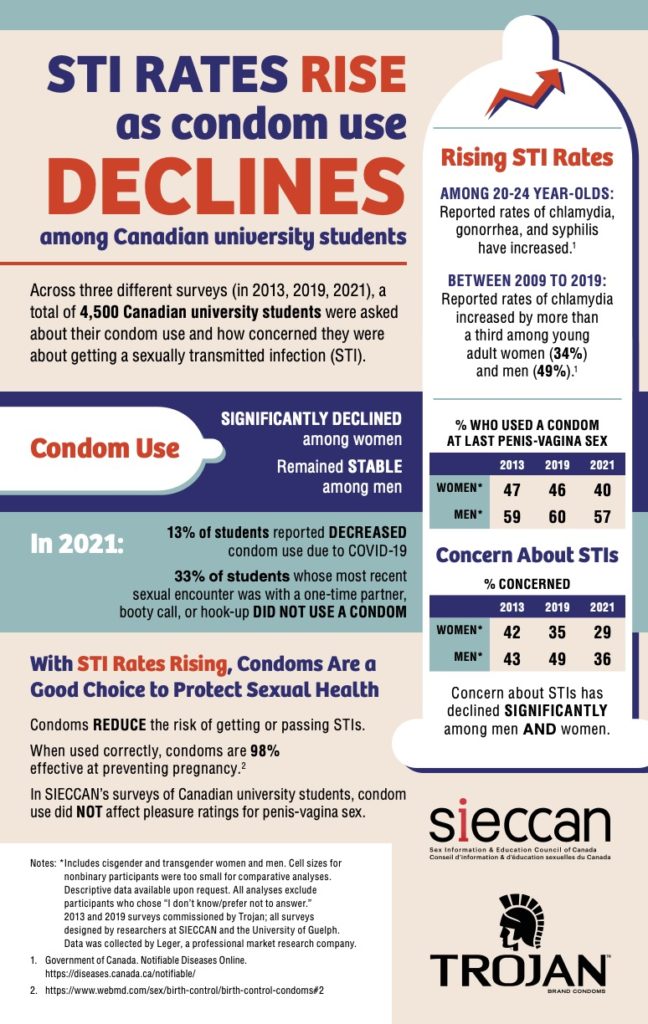

This interview provides greater context to a survey conducted by SIECCAN in partnership with Trojan Condoms. 4,500 Canadian university students were asked about their condom use and how concerned they were about getting a sexually transmitted infection (STI). The infographic is presented at the bottom of the interview questions.

What are some of the major factors contributing to the increase of STIs among Canadian University students?

There are numerous factors that likely contribute to increasing STI rates among young adults in Canada. Importantly, these are reported rates, which are impacted by increased testing and more sensitive tests. That is, reporting methods and better tests could be one factor that accounts for why we see steadily rising rates, in addition to other factors.

One issue our research (which was conducted in partnership with Trojan Condoms) highlights is that most university students are not concerned about STIs. This may reflect a need for more comprehensive sexual health information in university settings to ensure that students are aware of how common STIs are, that most cases of STIs are asymptomatic, and that they know how to access STI testing services.

It may be that overall awareness about STIs is currently lower. For a long time, educational awareness efforts focused on HIV prevention, with emphasis on barrier use. As HIV infection rates have stabilized, there has been less public attention focused on HIV and, as a result, may be leading to decreased condom use among young people. We also now have PrEP and PEP to reduce the risk of HIV, which is excellent. However, the availability and use of these medications may also be contributing to decreased condom use. It is important to educate people on the importance of continuing to use condoms and having regular STI screens while using PrEP.

We may need to increase and/or shift our educational approaches to engaging with young people around STI awareness and prevention to ensure that STIs are on their radar and to debunk any myths or misconceptions.

You mentioned that your research showed a decline in concern around STIs among students. Why do you think this is and do you have any additional data and/or explanation as to why students are becoming less concerned about STIs?

I think the answer to #1 above regarding STI misconceptions gets at this question! Rising STI rates and a lack of concern about STIs are likely quite interrelated. Students may not be concerned about STIs because they do not perceive themselves as being at risk of getting or passing an STI due to common misconceptions that can be addressed through comprehensive sexual health information.

For example, young people may not realize that they can get or pass an STI when they don’t have any symptoms; there’s also an assumption that when you are in a monogamous relationship, you don’t need to be tested for STIs or don’t need to continue to use barriers, like condoms. However, it’s possible for someone to enter a relationship and not know that they currently have an STI and then unknowingly pass it to their partner. People may also be having lots of different types of sex and not know what the risk of getting or passing STIs is for specific sexual behaviours. They may think that STI prevention and safer sex methods isn’t something that they need to worry about.

How do these survey findings compare to national statistics on STI rates and condom use among the general population? Are there any similarities or major differences between the trends seen amongst university students and the general population in Canada?

Note: The STI rates presented in the SIECCAN and Trojan infographic are drawn from the Government of Canada’s Notifiable Diseases Online tool (i.e., they are national statistics of 20–24-year-olds in Canada).

Generally, in the research we see that condom use declines with age, even among younger people (Fetner et al., 2020; Roterman & McKay, 2020). For example, research using data from the Canadian Community Health Survey reported that 79.9% of 15–17-year-olds used a condom the last time they had sexual intercourse; this number dropped to 67.3% for 18–19-year-olds, and 55.1% for 20–24-year-olds (Roterman & McKay, 2020).

Research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic is one of the reasons condom use has decreased among university students. Why is that?

I think we need further research to answer this question. In our research, many students reported having partnered sex less frequently during the pandemic. However, some participants also said that their access to condoms had decreased due to the pandemic. If university clinics were a key place for students to get condoms, it would have been difficult for them when these facilities were no longer available or if they had to move home and perhaps didn’t have as much privacy to order/receive them from an online source. As our guidelines change and people begin to reengage with sex partners, it is going to be critical that young adults have easy access to condoms to prevent STIs.

Why is the data showing that condom use among women has dropped significantly more than among men?

I think there are likely many factors contributing to a decline in condom use. One factor that may explain the decline in use among women could be related to changes in contraceptive options. Our studies suggest that undergraduate ciswomen are often motivated to prevent pregnancy and are not as focused on or as concerned with STI prevention. In the 2019 survey we asked students what their main reason was for not using a condom and 46.3% said that “I/my partner use/uses a different form of birth control.” This is similar to what Statistics Canada has reported: 47.2% of 15–24-year-olds said that they did not use a condom during their last sexual encounter because they “used another method” (Roterman & McKay, 2020). It is wonderful that we now have so many great contraceptive options for people to choose from. However, it’s also important that people are informed about whether the contraceptives they are using also help to prevent STIs and if not, that they are given information about how to integrate STI prevention methods into their sexual lives.

Also, there’s often a concern or an assumption that condoms will reduce pleasure during sex. We have not found this to be the case in our research. In our studies, condom use does not seem to impact pleasure ratings for sex: there’s no significant difference in the percentages of people who say their last sexual experience was “very pleasurable” based on whether or not they used a condom.

What can healthcare professionals do to help increase awareness and knowledge of STIs? How can healthcare professionals ensure that their clients are fully informed about the risks associated with STIs?

Health care providers play a pivotal role in delivering sexual health information and services to young people. They are often the first point of contact for sexual health concerns and are viewed as highly authoritative sources of information. It is critical that HCPs are up to date on sexual health information, particularly as it relates to STI prevention. HCPs should be familiar with STI prevention as it pertains to a range of sexual behaviours and relationship configurations to adequately inform patients and give them information that meets their specific needs (e.g., whether someone is in a monogamous relationship, a consensually non-monogamous relationship, or single; whether someone is in same or other gender partnerships or both etc.). This might mean engaging in ongoing training and professional development related to sexual health.

STI-related stigma may also play a role. If someone feels judged or shamed for having an STI or having had one in the past, this could impact communication with partners or health care providers, and whether someone gets tested and treated. This is another reason why education is critical – normalizing information about STIs and safer sex options is one step towards breaking down the stigma related to STIs.

How can healthcare professionals better educate clients about safer sex practices and ensure students have access to safer sex materials?

Ensuring that there is adequate time to ask questions, develop trust with patients, and deliver information and services in a non-judgmental way is key. HCPs should not assume that university students have received adequate sexual health education by the time they get to university and should continue to provide students with access to relevant, evidence-based information. HCP can also link students to other sexual health information resources both on and off campus (e.g., sexual health information websites, counselling services, gender-based violence support services, etc.). It is also important to remember that STI prevention includes discussion on how to talk to sex partners about barrier use or other forms of safer sex.

What can healthcare practitioners do to increase awareness and access to STI/STBBI testing for students?

Continued and enhanced access to sexual health information and services for young adults will be especially important as we move out of the pandemic; about one quarter of university students in our most recent survey reported decreased access to STI testing and services and decreased access was more pronounced for women and students of colour. Health care providers can advocate for and help to ensure that students have access to consistent and equitable access to sexual health information and care that is relevant to their needs.

References:

1. Fetner, T., Dion, M., Heath, M., Andrejek, N., Newell, S. L., & Stick, M. (2020). Condom use in penile-vaginal intercourse among Canadian adults: Results from the sex in Canada survey. Plos one, 15(2), e0228981.

2. Rotermann, M., & McKay, A. (2020). Sexual behaviours, condom use and other contraceptive methods among 15-to 24-year-olds in Canada. Health Reports, 31(9), 1-11.